A Pandemic of Faith

It may seem too soon to see hope. It is. And it isn’t. First, we have to allow ourselves room to name and experience grief. We have lost a lot. This pandemic is showing us all what folks at the margins of our capitalist system experience daily: lack of food, not enough income to pay rent, not having access to the supplies we want or need, lack of access to medial care. For many of us, we are experiencing a profound amount of insecurity—a looming darkness in our consciousness so heavy and opaque that it numbs us or weighs on our spirits inducing anxiety and uncontrollable fear. It’s healthy to begin by naming these emotions.

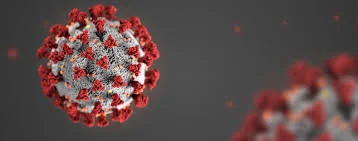

It’s been three weeks since the U.S. recognized the seriousness of COVID-19 and began suggesting physical distancing. At first, my closeted introverted self was alright with flying solo for a while, but this gouging of physical interaction has changed our world more than I expected. And what’s even more strange is that that last statement isn’t an exaggeration—our world is drastically different today than it was three weeks ago, and the Church will be too.

I remember teaching my grandmother how to FaceTime 5 or 6 years ago. Touching a glass screen and seeing another face seemed so odd and unfamiliar, but it was something fun to try. Now, it’s the only way for us to safely communicate (though I admit I should FaceTime her more often… Sorry, Grandma!). Classes, family dinners, meetings, birthday parties, and even worship services are all going online. Everything I took for granted in our interconnected world has had to shift to a virtual medium. Many important questions have arisen from this strange moment we find ourselves in and we can be sure that academics, influencers, bloggers, and even your grandparent will be talking about this for years.

One of the most important changes I’ve experienced is a new awareness of the value of community. This moment has led many to interrogate sociological questions like: how are communities defined and constructed, how do we identify who our people are if it’s no longer about geographical location or which grocery store we enter (Walmart or Trader Joe’s)?

This moment also beckons forth the need for powerful theological reflection on everything from the sacraments (is it still real communion if the pastor’s hands don’t physically wave over your bread and juice?) to the very identity of what it means to be the church when we can’t physically gather together in a sanctuary. This is HUGE. And confusing. And scary. And, it’s also exciting.

After we’ve allowed ourselves space to grieve—and continue name this emotion as often as it emerges—we’re able to see the glimmers of hope and potential good that we can make together from this experience. As many Christians often say, “We’re Easter people!” Even in the midst of Lent’s 40 days of reflection which begins with the solemn remembrance of our mortality on Ash Wednesday, the Sundays of Lent are mini-Easters—otherwise Lent would be 46 days. Our liturgical calendar of the Church is organized in such a way that we should be uniquely familiar with experiencing hope in the midst of long periods of despair.

Have you experience a mini-Easter during the days of Lent 2.0/COVID-19? Have you allowed yourself to not feel guilty for taking a day off or for looking for the glimmers of hope that can come from this collective experience?

Over the coming weeks, I’m looking forward to spending my mini-Easters by reflecting on how this moment will impact the Church around the world for the better and writing these thoughts on my neglected blog page. Stay tuned, and stay safe!